A working model of suicide prevention

Said Shahtahmasebi, PhD

correspondence: radisolevoo@gmail.com

Received: 12/2/2017; Revised: 15/3/2017; Accepted: 20/3/2017

1. Introduction

Mortality due to suicide data is routinely available for most countries from the national mortality data or from a coroner’s office. In most health service information systems mortality by age, gender, and ethnicity is also routinely available.

An examination of a selection of governments’ suicide prevention websites and documents and other suicide prevention agencies (e.g. New Zealand, US) demonstrate the emphasis placed on suicide mortality and the urgency to act in order to reduce suicide rates.

The reader may wonder why this point merits discussion, after all statistics are useful in informing and triggering appropriate action.

Indeed, routine suicide data have been informing for over a century: we know, for example, there are ethnicity, age and gender differentials in suicide rates, we know suicide trends follow a cyclic pattern, we know that there is a lag effect between suicide trends for age, gender and ethnicity – these examples should potentially inform policy formation, but, “who” is paying attention?

Judging by the fact that, at least in New Zealand, Australia, UK and USA, the suicide prevention strategy has not changed, and is still emphatically based on the notion that suicide is the result of a mental illness/depression, there is only one conclusion to be made.

The simplistic notion that suicide is the outcome of mental illness/depression has been challenged before (Hjelmeland et al., 2012; Pridmore, 2009; Pridmore & Walter, 2013; Shahtahmasebi, 2013a, 2013b, 2014a), most recently in a WHO document (WHO, 2014), but is anyone paying attention?

The fact is that focusing on mental illness as the cause additional resources are diverted and allocated to mental health services, e.g. the Minister for Health’s response to the recent rise in suicides (again) in New Zealand was that mental health services provision must be strengthened. There is only one conclusion to be made.

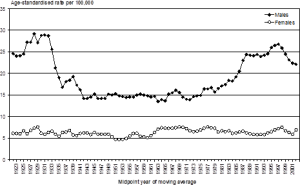

It appears that medical modellists and decision makers take credit only at the end of a cycle when suicide rates trend downward, i.e. claiming that the reduction in suicide rate is because of mental health interventions but have no explanations to offer at the beginning of the cycle when the trend is upward. So, as shown in Fig.1 the claim of a causal relationship between mental illness and suicide is false due to a number of short-, medium-, as well as long-term cycles in suicide trends since record keeping began. This pattern suggests that suicide rates have not been influenced by past and current beliefs that mental illness/depression is the cause of suicide (Shahtahmasebi, 2013b). So why do we insist on sustaining failed models, and why is no one paying attention? The answer, most likely, lies in politics (Shahtahmasebi, 2013a).

Figure 1. Death from suicide by sex, New Zealand, 1921-2003.

Source: New Zealand Health Information Service (Ministry of Health, 2006).

Exploring conflicting trends suggest that suicide trends by any groups such as by gender or age groups follow the same cyclic pattern (Shahtahmasebi, 2013a). A comparison of such trends also suggests that there is a lag-time between group cycles, e.g. male suicide rates are almost half a cycle ahead of that of females. This explain the news headlines every now and then announcing a group having high risk of suicide, e.g. the most recent report that male construction workers are at greater risk of suicide (see https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/mar/17/male-construction-workers-greatest-risk-suicide-england-study-finds?CMP=share_btn_link).

The suicide literature continues to demand more data, while indigenous populations are demanding more accurate indigenous suicide mortality data, but what is the point of more data if past behaviour shows we continue to ignore the data?

2. Ignorance: suicide data vs medical hearsay

It is a mystery as to why people would choose death over life and kill themselves. We have never understood why and we probably never will. There have been many theories to explain suicide and thus inform the process of policy development in order to prevent suicide, e.g. cultural and traditional explanations (Pridmore & Walter, 2013), the ugly duckling scenario where an individual is made to believe they do not belong to their community (Shahtahmasebi, 2013a), inability to confront and deal with life predicaments (Pridmore et al., 2016; Shahtahmasebi et al., 2016), being out of their mind to want to kill themselves, or a most recent addition that asserts the presence of ‘pain’ that consumes the individual to the extent that death is the only solution, which is termed ‘psychache’ (Ellis, 2006; Klonsky & May, 2015; Shneidman, 1993). The problem is, of course, that with suicide the only person who could explain their process of decision making to die is no longer alive. Therefore apart from suicide mortality data, i.e. number who have died as a result of suicide, suicide data is often vague, biased and irrelevant and inappropriate for decision making. After all, the suicide discourse emphasizes the choice between life and death. In other words, suicide is the outcome of the process of decision making.

In the Western world, however, suicide prevention is firmly based on the presence of depression and/or a mental illness. In most cases when a government policy fails or is not performing well it is scrapped and replaced. This does not happen with suicide prevention, or indeed with any other prevention strategy for heart disease, cancer and mental illness. On the contrary, the emphasis on mental illness causing suicide appears to become stronger at every reported suicide and every time the suicide rate increases. It is of no surprise that suicide is still one of the top causes of death. Thus decades of Western style suicide prevention provide ample evidence that suicide prevention policies based on mental illness do not work.

Contemporary suicide research, on the whole, has ignored historical evaluations of suicide research and suicide prevention using historical data and observations. Psychological autopsies and suicide research that attempts to understand suicide from information gathered from significant others after the event of suicide have been challenged and rendered useless (Hjelmeland et al., 2012; Pridmore, 2009; Pridmore & Walter, 2013; Shahtahmasebi, 2013a, 2013b, 2014a).

Clearly, collecting information from third parties about a case after the event of suicide, it is highly likely that there will be a strong mental illness bias in their responses. Secondly, such research is psychiatric oriented from the outset, therefore it is highly likely that the responses will be mental illness biased. Thirdly, the study design does not account for bias and fails to acknowledge the above substantive issues arising. Fourthly, the statistical methodology and analysis also fails to account for bias. Therefore, the results from such studies will be heavily inflated and biased towards mental illness as the cause of suicide (see also (Shahtahmasebi, 2014a)). Thus, diverting or limiting funds from other research that could potentially lead to working models of suicide prevention.

Despite the evidence psychiatric oriented suicide prevention research still continues to attract the entire suicide resources, including the media. In addition the social suicide discourse is dominated by mental illness. There have been many attempts to encourage the public to seek help for depression. In the most recent initiative stars of New Zealand rugby opened up and shred their battles with depression publicly (e.g. see http://www.nzherald.co.nz/sport/news/article.cfm?c_id=4&objectid=11819721) – in all such initiatives and media reporting of them suicide and depression are used interchangeably as though they are one and the same.

The size of the population of people with mental illness/depression, psychache, life predicaments is not known but the assumption is that it is quite large, yet, the proportion of people in such situations who actually commit suicide is very small. Statistically, it is not possible to show a cause and effect or a correlation between the various conditions and suicide. For example, a study of records in a psychiatric hospital (Shahtahmasebi, 2003) revealed that the largest proportion of patients who died by suicide (33%) had no psychiatric diagnosis. Furthermore, the study revealed that suicide under psychiatric care formed only one-third of all suicides – this means that in addition we do not know anything about the two-thirds of suicide cases who did not seek psychiatric help.

The ‘mistake’ that scholars, politicians and decision makers make is to assume causality that does not exist or is very weak rather than ask the more appropriate question as to why when people with similar characteristics facing the same issues and problems some may commit suicide whilst others do not.

One outcome of promoting unproven causal relationships is to influence the public mindset and unwittingly make suicide socially acceptable. In a recent study of public attitudes to suicide it was revealed that suicide may be a well-established ‘solution’ to life difficulties/predicaments in the public mindset (Pridmore et al., 2016; Shahtahmasebi et al., 2016). In this study 647 individuals from 35 countries were presented with a set of scenarios in which fictitious characters faced predicaments varying in severity and were asked if the individual would have suicidal thoughts/intentions. Two major observations from this study are that, first, there were only two comments raising objection to suicide being a solution to problems. Second, the proportion of respondents agreeing with suicidal intentions increases with the severity and complexity of the predicaments. For example, in the above study respondents were presented with a scenario featuring a fatal road accident caused by the driver swerving to avoid a child and killed an adult on the other footpath, and respondents were asked if the driver would have suicidal thoughts. For this scenario 45% of the respondents moderately or strongly agreed that the car driver would have suicidal thoughts. Next, respondents were presented with a more complex scenario where the fatal accident was caused by a speeding drunk driver who insisted on driving after a party – under this scenario 68% of respondents strongly or moderately agreed that the driver would have suicidal thoughts.

The second problem is associated with making conclusions based on poor research and inappropriate data. Suicide research, such as psychological autopsies, have been used to claim that 80-90% of all suicides had depression. This claim is totally wrong (Shahtahmasebi, 2013b; WHO, 2014) and serves only one purpose: to strengthen the medical modellists’ grip on suicide funds.

The net effect of a medical intervention to prevent suicide is the vicious circle in which mental illness is always the cause of suicide so the only action that can be taken is more psychiatric interventions. In other words, this strategy has amounted to a ‘more of the same’ policy, but at a much higher cost in the lives lost to suicide and in monetary terms.

The third problem is associated with mis-interpretation of data and generalization of results to the general population, leading to erroneous policies. For example, in New Zealand there is a policy restricting the reporting of suicide in the media, in particular the method of suicide. Quite apart from the fact that anyone with access to the internet can easily read about method of suicide as well as web sites promoting or reporting on particular methods of suicide. The net effect of this policy has been to push any discussion of suicide out of the public domain and which in turn continues to emphasize and maintain the taboo status of suicide. Furthermore, without any leadership by the New Zealand Government, the policy has been misinterpreted by various organisations including schools so that suicide cannot be mention at work or at schools. Once more there is no evidence to support a policy of silence and secrecy around suicide (Shahtahmasebi, 2014a).

3. The problem with the medical model as a suicide prevention strategy

As a starting point, strategies based on medicalization of suicide aim to prevent suicide by looking for signs of mental illness and apply appropriate psychiatric treatments thus preventing suicide. The guidelines encourage the public to look for signs of mental illness/depression and refer to mental health services. The main problems with such a strategy are:

- Signs of mental illness are only detectable after it has developed, if mental illness is responsible for suicide then it would be too late to prevent but there may be time to intervene.

- Between two-thirds and three-quarters of suicide cases had no contact with mental health services (Hamdi et al., 2008; Shahtahmasebi, 2003).

- How does the above method identify those with mental illnesses who do not exhibit symptoms or are good at hiding them?

- Between one-quarter and one-third of suicide cases have had at least one contact with mental health services – and yet went on to complete suicide whilst under psychiatric care or within forty-eight hours of discharge.

- The medical model attempts to treat a mental illness that may or may not exist in suicide cases.

- By law all suicide attempters have to be assessed by a psychiatrist before discharge. And since psychiatrists look for signs of mental illness as the cause of suicide the victim is categorized as a low or no suicide risk if there are no signs, and discharged. So, suicide attempters are returned to their communities to the same circumstances and/or life predicaments that drove them to suicide in the first place. Inevitably, a proportion of the attempters will continue to attempt until successful.

- Finally, and more importantly, this method ignores suicide by concentrating on finding a psychiatric diagnosis for which a course of treatment can be prescribed – thus adding to the suicide statistics.

Therefore, as an intervention, the medical model fails to prevent suicide.

4. A working model for suicide prevention

It is interesting that health care professionals/service providers along with academics and politicians/decision makers have never raised concerns about the need to wait for an outcome before instigating an intervention. I am urging colleagues and anyone who cares about suicide prevention to provide a satisfactory reply to this question:

If mental illness is the cause of suicide then why do we wait for mental illness to develop before action is taken?

To use the gun analogy, it is too late to stop the bullet once the trigger is pulled, it would be more effective to remove the gun in the first place. In other words, it would make more sense to have a well-developed mental health care system that is responsive – currently mental health services globally and nationally are not responsive (Shahtahmasebi, 2012), and anecdotal evidence suggests that in New Zealand the perception is that the only way to see a psychiatrist is to attempt suicide (Shahtahmasebi & Smith, 2013).

The only conclusion to make is that the medical fraternity itself doubts the effectiveness of this model of suicide prevention.

To develop a successful suicide prevention strategy we must take a step back and consider and evaluate our knowledge of suicide and adopt a multi-dimensional view in which all stakeholders and all identified parameters are taken into account. In other words, the simplistic one dimensional and flat view of a possible link between mental illness and suicide can be part of a more complex web of parameters influencing the process of individuals’ decision making to live or to die (Shahtahmasebi, 2013a).

As mentioned earlier, there is ample evidence that scholars, professional care services and the New Zealand Government have persistently and consistently continued with the belief that mental illness causes suicide and only medical services can prevent suicide. As a direct result of this stand other problematic issues have developed such as the severe adverse effect on suicide survivors (Shahtahmasebi, 2014b), and suicide silence where mentioning suicide prevention openly and without the presence of a psychiatrist may lead to disciplinary action by employers, or frontline workers being threatened with disciplinary action if they attend alternative suicide prevention training/seminars.

Therefore, a policy of ‘more of the same’ with no real effect on halting rising suicide numbers and the inability to care for suicide survivors (family, relatives, and friends) is conducive to mobilizing the public to take action. But for such actions to be effective they need support and appropriate and relevant information.

The grassroots approach to suicide prevention has been discussed elsewhere (Shahtahmasebi, 2013a). The grassroots strategy was implemented with no financial help from any Government agency but was supported by local charities in the communities that participated.

The strategy works through community empowerment by providing access to appropriate and relevant suicide information. Grassroots know more about their communities than detached scholars and decision makers. In the main centuries of evidence prove that we do not understand suicide but we have made substantial gains in understanding human behaviour. Through community empowerment, behaviour can be modified to change a decision to die into a decision to live, as illustrated by the substantial reduction in suicide, in particular youth suicide, in the communities that participated (Shahtahmasebi, 2013a).

References

Ellis, T. E. (2006). Cognition and suicide: Theory, research, and therapy: American Psychological Association Washington, DC.

Hamdi, E., Price, S., Qassem, T., Amin, Y., & Jones, D. (2008). Suicides not in contact with mental health services: Risk indicators and determinants of referral. J Ment Health, 17(4), 398-409.

Hjelmeland, H., Dieserud, G., Dyregrov, K., Knizek, B. L., & Leenaars, A. A. (2012). Psychological autopsy studies as diagnostic tools: Are they methodologically flawed? Death Studies, 36(7), 605-626.

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2015). The three-step theory (3st): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8(2), 114-129.

Ministry of Health. (2006). New zealand suicide trends: Mortality 1921-2003, hospitalisations for intentional self-harm 1978-2004 (No. Monitoring Report No 10). Wellington: Ministry of Health, New Zealand.

Pridmore, S. (2009). Predicament suicide: Concept and evidence. Austral Psychiat, 17, 112-116.

Pridmore, S., Varbanov, S., Aleksandrov, I., & Shahtahmasebi, S. (2016). Social attitudes to suicide and suicide rates. Open Access Journal of Social Sciences (JSS), 4(10), 39-58. URL: http://www.scirp.org/Journal/PaperInformation.aspx?PaperID=71256.

Pridmore, S., & Walter, G. (2013). Culture and suicide set points. German J Psychiatry, 16(4), 143-151.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2003). Suicides by mentally ill people. ScientificWorldJournal, 3, 684-693.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2012). A review and critique of mental health policy development. Int J Child Health Hum Dev, 5(3), 255-264.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2013a). De-politicizing youth suicide prevention. Front. Pediatr, 1(8), http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fped.2013.00008/abstract.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2013b). Examining the claim that 80-90% of suicide cases had depression. Front. Public Health, 1(62).

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2014a). Suicide research: Problems with interpreting results. British Journal of Medicine and Medical Research, 5(9), 1147-1157.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2014b). Suicide survivors. Dynamics of Human Health (DHH), 1(4), http://www.journalofhealth.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2014/2012/DHH_Said_Survivors.pdf.

Shahtahmasebi, S., Pridmore, S., Varbanov, S., & Aleksandrov, I. (2016). Exploring social attitudes to suicide using a predicament questionnaire. Open Access Journal of Social Sciences (JSS), 4, 58-71.

Shahtahmasebi, S., & Smith, L. (2013). Has the time come for mental health services to give up control? J Altern Med Res, 6(1), 9-17.

Shneidman, E. S. (1993). Commentary: Suicide as psychache. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 181(3), 145-147.

WHO. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/..