Suicide prevention strategy: buzzwords and personal opinions

Said Shahtahmasebi, PhD.

The Good Life Research Centre Trust, Christchurch, New Zealand

Correspondence: radisolevoo@gmail.com

Key words: Suicide, suicide prevention, culture, feel good,

Received: 31/5/2019; Revised: 15/6/2019; Accepted: 25/6/2019

[citation: Shahtahmasebi, S. (2019). Suicide prevention strategy: buzzwords and personal opinions. DHH; 6(2):http://www.journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=1838]

Abstract

Whenever a government policy is announced with razzmatazz and buzzwords and hailed a success even before its implementation then it is almost always a sign that the policy offers no new ideas or new methods of tackling a persisting issue. Suicide prevention is no exception. After decades of funding the mental health service on suicide prevention amidst rising suicide rates, in its 2019 budget the New Zealand government committed even more funds to the mental health service and called it a “wellbeing” budget. In announcing its “wellbeing” approach to budgeting the government allocated $1.9 billion to the mental health service. This approach to suicide prevention is based on a nine months inquiry into mental health and addiction. Unsurprisingly, the New Zealand government has failed to remove the boundaries on suicide by encapsulating suicide within mental illness, thus, making the development of a workable suicide prevention strategy impossible. This framing has cemented suicide prevention in a small and inflexible black box from which there is no escape. That is to say, the boundaries of suicide and suicide prevention are closed off to other processes such as social, economic and health, therefore, denying the dynamic influence from such processes. As a result the public will be given “more of the same” mental illness intervention regardless of the amount of resources invested in the mental health service. What is the point of labelling the national budget the “wellbeing” approach when the rest of the government’s social, health, economic, education and environment policies are discriminatory? In this paper I examine the government’s “wellbeing” approach to suicide prevention and how it appears that the only connection with “wellbeing” is the focus ($1.9 billion) on mental illness.

Suicide numbers vs suicide rates

The suicide numbers released by the Chief Coroner’s office in 2018 were a record high for the fourth year running (Stuff.co.nz, 2018). Of course, the muted response to record high suicides numbers four years in a row may be public apathy and fatigue (Shahtahmasebi, 2018a, 2018b). Anecdotally, the record high numbers have been played down by highlighting the increase in population size. In other words, although suicide numbers have gone up so has the population, and therefore, it is claimed, that proportionally relative to the previous year, suicide mortality has not changed much. The government has taken comfort in this argument in order to persevere with its “more of the same” suicide prevention strategy by investing even more in the mental health service. I will briefly deal with this unwise assumption.

Apart from the record numbers of suicides the main issue of concern is the fact that the suicide rate has been trending up for a number of years especially over the last four years. In general, it is expected that the frequency of an event increases as the population size increases. Under this concept, the numbers of an event, e.g. number of deaths due to heart disease or suicide is presented as a proportion of the population in order to compare annual morbidity and mortality with previous years. These statistics are useful for resource planning but they are a major distraction from addressing the reasons for the increase in mortality or morbidity. But we have no idea how many or what proportion of the events were actually from the new portion of the population (e.g. newly settled immigrants, new births, returnee expatriates). Furthermore, for decades there has been a massive drive to reduce morbidity and mortality numbers therefore we would expect them to go down over time, especially as a proportion of population. But morbidity and mortality rates e.g. due to heart disease, cancers and suicide have been trending up. In other words heart disease, cancers and suicide are still the top causes of deaths (CDC, 2017).

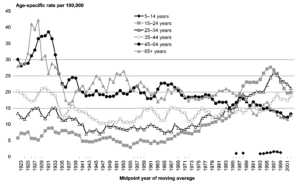

Substantively, this argument is unjustified, at least in the suicide context. There was a time where, there were either none or a very small but constant number of adolescent suicides from one year to another despite possible increases in population size (e.g. see Figure 1). Furthermore, as demonstrated in Figure 1, suicide rates/numbers follow a cyclic pattern, i.e. a period of upturn followed by a downturn despite an increasing population size.

Figure 1 – New Zealand long-term suicide rates by age

This means that, at least in part, suicide is independent of population size. Firstly, New Zealand’s suicide rates are the highest in the OECD and EU countries (BBC, 2017). Secondly, according to Statistics New Zealand the population has been increasing, e.g. from 3,732,000 in 1996 to an estimated 4,885,300 in June 2018 (Statistics New Zealand, 2019). But over the same period suicide numbers/rates dipped before rising – a pattern that has been repeating over time – and decades of suicide strategies has failed to break this cycle. Therefore, instead of understanding and addressing suicide (or any other adverse outcomes) we are locked in a perpetual motion of collecting mortality data, presenting them as proportions of population and proportionally allocate limited resources without impacting morbidity and mortality rates.

Misguided focus

In New Zealand when suicide numbers reached a new record for the third year running in 2017, the Government’s response was that we need to strengthen our mental health service (again) and pledged more funding, promising an inquiry into the mental health service. In other words, the government missed the biggest opportunity to be innovative and visionary and made the same mistakes made by its predecessors. The mistake committed here is the assumption that suicide is a mental illness. The Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry was established in January 2018 and finally reported its findings in November 2018 (Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry, 2018) during which suicide numbers reached another record high for the fourth year running. A critical analysis of the Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry in relation to suicide prevention is reported elsewhere (Shahtahmasebi, 2019). Suffice to say that the Inquiry’s recommendations to reduce suicide numbers were limited to mental illness and included an immediate national suicide prevention strategy, investing more in the mental health service, and better access to mental illness services. In this paper I question the relevance and value of a “wellbeing” approach to suicide prevention.

The “wellbeing” approach

The New Zealand government, in the 2019 budget (radionz.co.nz, 2019b) announced its “wellbeing” budget under the theme “taking mental health seriously” in which it had accepted most of the Inquiry’s recommendations. In this budget the government has committed $1.9 billion to the mental health service out of which $40m will be dedicated to address the record number of suicides. This fund will go towards a new suicide prevention strategy that is a recommendation of the Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry and is being worked on by the Health Ministry.

The key words are “wellbeing”, “$1.9 billion”, “suicide prevention strategy”, “Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry’s recommendation”, “new suicide prevention strategy”, “being worked on”.

As discussed above, suicide is framed as a mental illness and resourced accordingly. As such, apart from the higher financial investment the “wellbeing” budget is no different to previous governments’ attempts to tackle the suicide problem. For example, it ignores the evidence from Australia that a “better access” policy of making mental illness interventions more accessible had no effect on their suicide rates (Jorm, 2018).

As predicted, by framing suicide as mental illness the government has closed off all doors and windows to vision and innovation, quantified “wellbeing”, and above all produced “more of the same” mental illness intervention at an unprecedented high price. For example, while the government wasted time and resources on a limited inquiry to come up with the same recommendation as current policy, suicide numbers reached a record high for the fourth year running. Furthermore, as it was reported (radionz.co.nz, 2019a) the budget allocated $1.9 billion to the mental health service over five years; it aims to put trained mental health workers in doctors’ clinics, iwi health providers and other health services; $40m of the overall $1.9 billion to go towards a new national suicide prevention strategy; free counselling for up to 2,500 people: four sessions per person; and another $200m on new and existing schemes and expanding the nurses in schools scheme. As for Maori, the government pledges: to recognise the needs in Māori and Pacific communities, up to eight programmes will be funded to “strengthen personal identity and connection to the community”.

An important observation here is whilst the government is happy to quantify “wellbeing” fit for the general Pakeha population it has been vague about the Maori population. For example does “funding up to eight programmes” mean unlimited resources for each programme? Why up to eight programmes? Or alternatively does it mean Maori’s share of the budget would be leftover funds, if any, once the budget is allocated as prescribed above? So some immediate questions arise, for example:

- How is the governments “wellbeing” approach associated with the government budget pledges?

- How will the “wellbeing” approach lead to reducing suicide?

- If “wellbeing” is the intended outcome then how will “wellbeing” manifest in the population?

- How will it be measured?

The main questions here are how has “wellbeing” been defined? And is this definition at population or an individual level? What does it mean to be “well”?

It is apparent that the “wellbeing’s” only connection is through the focus on mental illness. “Wellbeing” is certainly a complex and dynamic process which cannot be simplified, quantified and measured easily. The criteria that may contribute and define one person’s, or a household’s, or a community’s higher levels of wellbeing may define others’ lower levels of wellbeing, e.g. one’s solutions may be another individual’s problem (Adams, 1985). An individual’s “wellbeing” whose current problems are financial with cumulative effects of inter-relating processes such as education, transport, accommodation, food security and so on will not respond well (or not at all) to (four sessions) counselling, and mental illness interventions regardless of the ease of access to such services. In other words, perceptions from lived experiences may positively (or negatively) influence the ability to problem solving (Isen, et al. 1987). Therefore, promising $1.9 billion to mental illness services with no accountability over a number of years will do nothing to prevent suicide other than raising public expectations – the feedback effect is of course that raised expectations and unmet goals will generate negative perceptions and lead to adverse social and health outcomes.

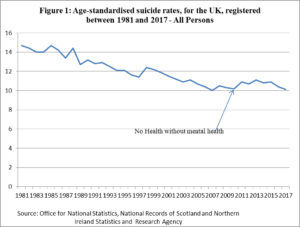

In 2011 the UK government implemented its long awaited white paper “no health without mental health” (Department of Health, 2011). By placing the emphasis on mental illness the UK government firmly defined wellbeing as a mental illness issue – doing the right thing for the wrong reasons. In terms of suicide prevention this policy had very little impact and suicides went up as shown in Figure 2 below.

In New Zealand, as mentioned above “wellbeing” has been equated to availability and access to mental illness services. The $1.9 billion budget is over five years and it will be some time before any changes in service delivery may be noticeable. So, will this level of funding lead to higher levels of “wellbeing” or simply slightly more access to mental illness services compared with previous years? In other words, the government has not specified how “wellbeing” will be measured, other than a “change” in the number of people using mental illness services.

Evidence from Australia in the form of “better access” to mental illness services which was introduced in 2006 does not equate to “wellbeing” leading to reductions in suicide numbers/rates (Jorm, 2018). The Australian evidence strongly suggest that “wellbeing”, suicide, mental health are separate processes that may influence each other indirectly through other processes, e.g. a caring society/community/family, availability and access to solutions/help, food security, and so on. A promise of financial intervention in someone else’s hand for a service that will not impact non-mental illness problems will not be therefore affecting suicide rates.

So what now?

It would seem that the New Zealand government’s $1.9 billion injection into the mental health service is more of a political decision with “wellbeing” and “taking mental health seriously” providing the buzzword to highly inflate the effects of the budget announcement. The comment made by a famous snooker commentator comes to mind “And for those of you who are watching in black and white, the pink is next to the green.” (The Telegraph, 2011).

In the past, governments defended their record on suicide prevention by claiming that they have invested additional resources in the mental health service (e.g. see (One News, 2017)). In defending itself the current government of New Zealand will boast of initiating an Inquiry and committing the largest investment ever in the mental health service. But apart from wisely rejecting the idea of setting up a target, the government’s response provides no new direction and no new ideas but only “more of the same” intervention at much higher cost.

As suicide numbers have been increasing over a number of years in New Zealand, the current cycle may be nearing an end, and it is highly likely that suicide rates will follow its cyclic pattern and the current upturn will sooner or later peak out and turn downward and once again the “experts” and the government will take credit for it until the cycle bottoms out and begins a new cycle. Unfortunately, every suicide that makes the suicide rates is somebody’s loved one.

To summarise, it seems that the invented buzzwords are more of a political “feel good” factor to cover up for a lack of substance (i.e. evidence) in policy. For example, the New Zealand’s 2019 budget is hailed as the “wellbeing budget” because of the focus on mental illness (radionz.co.nz, 2019b). In Australia the feel good factor was the “better access” to mental illness interventions policy (Jorm, 2018), and in the UK it was “no health without mental health” policy Figure 2 (Department of Health, 2011). In both cases suicide rates continued on an upward trend.

Buzzwords and symbolism do not save lives.

Suicide prevention need not cost much

A grassroots approach to suicide prevention empowers communities to take responsibility and ownership of the suicide problem and develop local solutions. In 2010 the grassroots approach was introduced by the author in Waikato, New Zealand, where there was huge interest from local communities (Shahtahmasebi, 2013)). These were communities with high rates of teenage suicide. Communities were given appropriate information about suicide and adolescent development and were empowered to own the suicide problem. The communities then came up with an action plan to combat suicide. The idea was that members of each community will know more about local issues than a politician based hundreds of miles away or medical modellists working from a university office, and therefore are able to devise local solutions to local problems. The upshot was that the communities that took part developed their own approach to suicide prevention and as a result the suicide numbers dropped substantially in these communities (Shahtahmasebi, 2013). This was achieved through sponsorship and empowering the communities to contribute to the suicide prevention efforts.

Concluding comments

What is the point of labelling the national budget the “wellbeing” approach when the rest of the governments’ social, health, economic, education and environment policies are discriminatory?

Suicide prevention has been bogged down with personal opinions of a number of medical modellists, furthermore, not one politician has been brave enough to break the cycle. Personal beliefs or statements by a senior politician, a scientific advisor, or a senior academic such as “mental illness and depression are causing suicide” are not strategies, they are not action plans, they do not add any insight nor do they contribute to the suicide debate. We are none the wiser; not only do we still not understand suicide, but also there has been no sustainable reduction in suicide rates; medium to long term suicide trends are generally upward.

It is total nonsense that any model can explain and then predict future suicide rates – the rising suicide rates across the globe provides strong evidence that we simply do not understand suicide. It begs the question why throw money at it? We do not even understand the cycles in suicide trends. This feature has been misused by the “experts”. When the cycle has peaked and is on a downturn, just as the current suicide rate will peak out sooner or later, it is claimed that suicide prevention policies are working and more funding is demanded to apply more of the same policies. And when the cycle is bottomed out and going up it is claimed that suicide is a very complex social and mental health problem and more funding is needed to reach out to more people, and for further research.

Complex multifactorial suicide can, at least in part, be explained by the clustering pattern in suicide rates. The cyclic pattern means that each suicide category e.g. age groups (adolescents/25-34/ etc), gender (male/female), occupations (farmers/pilots/doctors/ etc), mental disorder (bipolar, schizophrenia, etc), and so on, also follow a cyclic pattern but each has a different start and end cycle. There is a lagging effect between all groups – so while suicide may be trending down for some groups it will be trending up for others – or appears stationary for some other groups. In other words, suicide is examined from every perspective and the numbers are analysed according to age, gender, religion, socioeconomic and employment status, and geographical location, to name but a few. It is not surprising that if you look at data repeatedly, you will eventually come up with something which looks “significant”.

Major feedback effects of continuing with the mental illness model to reduce the New Zealand suicide rate have been, firstly, a lack of progress in our understanding of suicide beyond its dictionary definition, and secondly, we have made it such a complex problem that we are unable to resolve it. In other words, researchers, politicians, the public and other stakeholders have become part of the suicide problem.

Suicide and its prevention must be depoliticized, be taken out of the mental illness framework and discussed on its own merits.

References

Adams, B. N. (1985). The Family: Problems and Solutions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 47(3), 525-529.

BBC. (2017). What’s behind New Zealand’s shocking youth suicide rate? https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-40284130, accessed 13 May 2019.

CDC. (2017). 10 Leading Causes of Death by Age Group, United States – 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/leading_causes_of_death_by_age_group_2017-508.pdf, accessed June 9, 2019.

Department of Health. (2011). No health without mental health: A cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages. HM Government Retrieved from www.dh.gov.uk/mentalhealthstrategy.

Isen, A. M., Daubman, K. A., & Nowicki, G. P. (1987). Positive affect facilitates creative problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(6), 1122-1131.

Jorm, A. (2018). Australia’s ‘Better Access’ scheme: Has it had an impact on population mental health? Aust NZ J Psychiatry, 52(11), 1057-1062.

Mental Health and Addiction Inquiry. (2018). He Ara Oranga : Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction. https://mentalhealth.inquiry.govt.nz/inquiry-report/.

One News. (2017). ‘We’re doing as much as we can’ – Bill English defends National’s record on suicide prevention. https://www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/new-zealand/were-doing-much-we-can-bill-english-defends-nationals-record-suicide-prevention, accessed 18 June 2019.

radionz.co.nz. (2019a). Budget 2019 Health portfolio: Mental health a $1.9bn priority for health portfolio. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/390901/budget-2019-health-portfolio-mental-health-a-1-point-9bn-priority-for-health-portfolio, accessed 31 May 2019.

radionz.co.nz. (2019b). Wellbeing Budget: Laudable, but not transformational. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/390936/wellbeing-budget-laudable-but-not-transformational, accessed 31 May 2019.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2013). De-politicizing youth suicide prevention. Front. Pediatr, 1(8), http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fped.2013.00008/abstract. doi: 10.3389/fped.2013.00008

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2018a). Editorial: prevention blind-sided by intervention. Dynamics of Human Behaviour (DHH), 5(3), http://www.journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=1616.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2018b). Editorial: the blame game. Dynamics of Human Behaviour (DHH), 5(4), http://www.journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=1674.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2019). Editorial: Politics of Suicide Prevention Revisited. Dynamics of human health (DHH), 6(1), http://www.journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=1740.

Statistics New Zealand. (2019). Subnational population estimates (UA, AU), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996, 2001, 2006-18 (2017 boundaries). http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLECODE7541, Accessed 6 May, 2019.

Stuff.co.nz. (2018). New Zealand suicide rate highest since records began. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/106532292/new-zealand-suicide-rate-highest-since-records-began.

The Telegraph. (2011). Former snooker commentator Ted Lowe dies, aged 90. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/sport/othersports/snooker/8486469/Former-snooker-commentator-Ted-Lowe-dies-aged-90.html, accessed 18 June 2019.