A forecast model of NZ suicide trends suggest an upward trend and yet the government proposes to make more investment to provide more of the same failed mental illness approach to suicide prevention.

[Editorial] New Zealand’s Suicide prevention plan 2025-29: More gloss, no substance

Said Shahtahmasebi1 & Russell Gregory-Allen2

1The Good Life Research Centre Trust, New Zealand; 2 Russell Research

Correspondence: Said Shahtahmasebi, email: radisolevoo@gmail.com

Key words: suicide, forecasting, ARIMA.

[citation: Shahtahmasebi, Said & Gregory-Allen, Russell (2025). [Editorial] New Zealand’s suicide prevention plan 2025-29: More gloss, no substance. DHH, 12(1):https://journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=3145].

Introduction

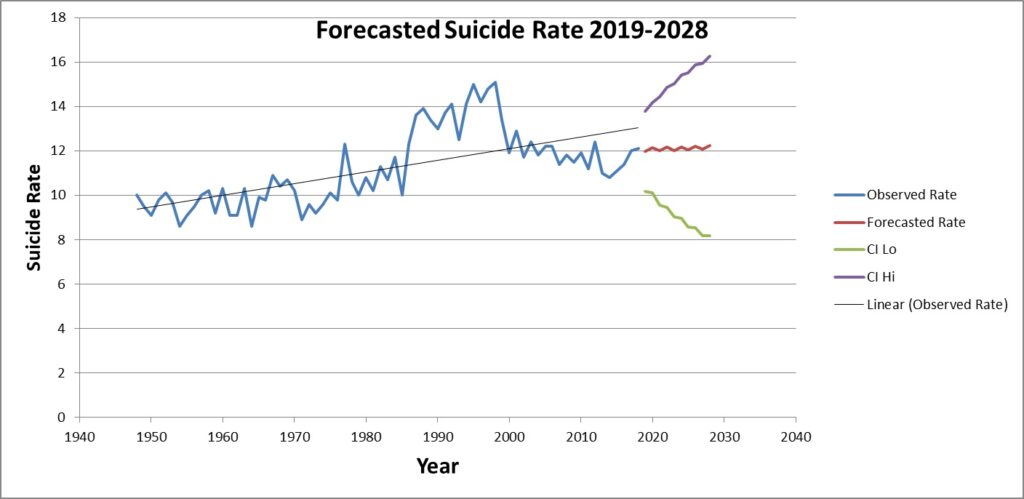

In 2023, DHH published an article which explored what might happen to suicide rates in New Zealand if we continue with the current suicide prevention strategy based on mental illness (Shahtahmasebi & Gregory-Allen, 2023). Historical suicide rates from 1948 to 2018 were used to forecast the suicide rates for the next 10-year period (2019-2028), see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The forecast suggested that while suicide rates may go up and down, overall they exhibit an increasing trend.

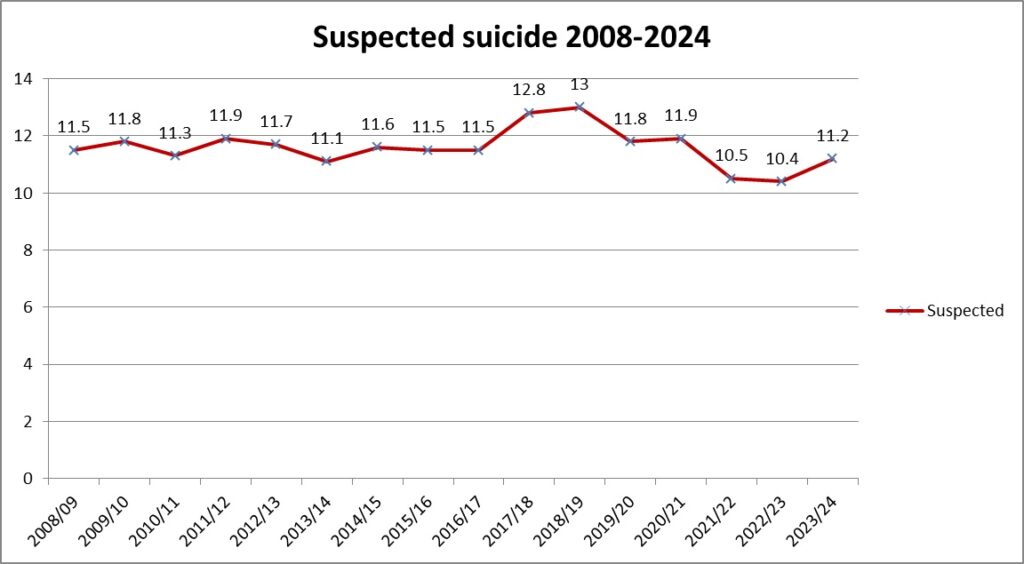

Since 2023 more suicide rates (2019-24) have become available (https://tewhatuora.shinyapps.io/suicide-web-tool/), these remain as suspected suicide until they have been confirmed by the coroner, See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

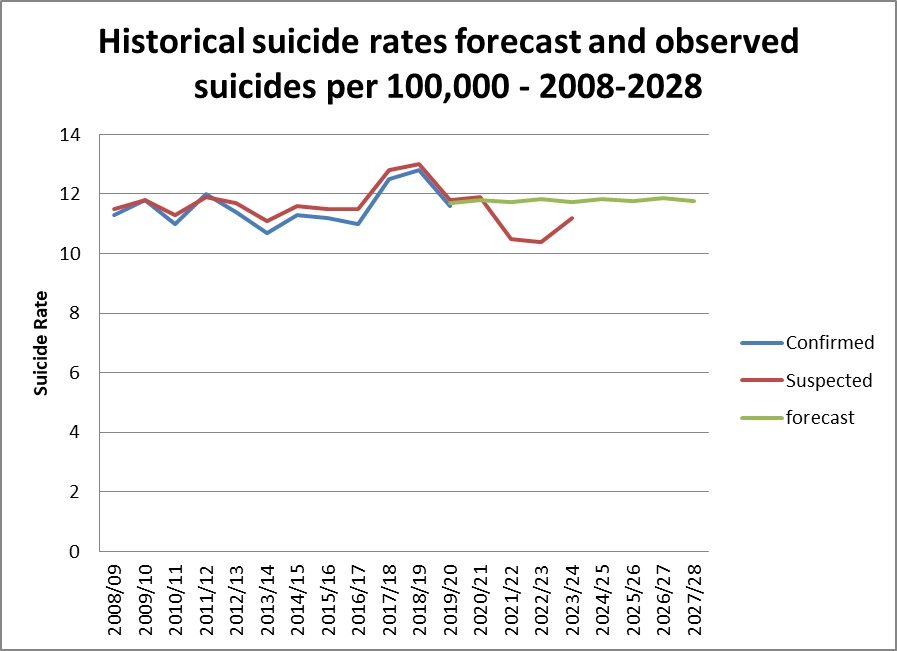

These rates are plotted on the forecasted graph, see Figure 3. It can be observed that the suspected suicide trend follows a similar pattern to that of the forecasted rates. Unfortunately, this similarity in patterns indicates that we should expect the upward suicide trends to continue to 2028 and beyond.

Figure 3.

In other words, mental illness based suicide preventions has failed to prevent and reduce suicide rates and will continue to fail. Nevertheless, we tend to persevere with the same failed policies (Shahtahmasebi & Gregory-Allen, 2023), hoping that one day a newly discovered mental illness disorder will explain suicide (Pridmore & Rostami 2020). In the meantime, someone’s loved one who has died needlessly by suicide is a very high price to pay for waiting for a disorder to manifest (Shahtahmasebi, 2013).

The process of developing a suicide prevention policy is further exacerbated by a common misconception/misinterpretation of the cyclic patterns in suicide rates. The policy of mental illness based prevention is credited with success when the cycle is peaked and going down, but no such accountability is assumed when suicide rates reverse and follow an upward trend. Instead, social and economic factors are blamed for the increasing suicide trends!

The question arises: what shall we do now?

The government issued a draft suicide prevention strategy and action plan in 2019 “Every Life Matters” (Ministry of Health, 2019), for a discussion of this strategy see (Shahtahmasebi, 2019a). The document states the strategy’s vision as:

“We believe that every life matters and, by working together, we can achieve a future where there is no suicide in Aotearoa New Zealand.”

The document then presents the “Every Life Matters” framework in a flowchart. Outcomes are defined as “reducing suicide” and “wellbeing for all”.

“Focus areas” of the policy are subtitled “building a strong system” with four elements: “National leadership”, “using evidence to make a difference”, “developing the workforce”, and “evaluation and monitoring”, that supports wellbeing and responds to people’s needs.

Clearly, based on these focus areas it can be concluded that this policy is not a suicide prevention strategy because it can only intervene if suicidality or a mental illness manifest. This strategy only allows medical intervention after an event, e.g. suicidality or depression, has occurred. Although, this policy document does not refer directly to mental illness, it would seem that “mental wellbeing” is the proxy for mental illness. Furthermore, it is not made clear what is meant by “developing the workforce”. In other words, what are the criteria for developing a workforce to perform what task, and how this will impact suicide rates. The only conclusion that can be made is that this solution involves addressing the shortage of psychiatrists/psychologists and mental health professionals.

Policy documents 2019-29 and 2025-29, like their predecessors reads like a wish list without any substantive support. Over decades of developing suicide prevention policies based on such sentiments there is no commensurate drop in suicide rates that the government can show. Surely, the only conclusion that can be made is that such policies are inappropriate and irrelevant.

On average, about two-thirds of all suicide cases do not have a psychiatric record or a psychiatric diagnosis (e.g. see Shahtahmasebi 2013, WHO 2014, CDC 2018) it then begs the question what the National Suicide Prevention Office, which was set up to promote national leadership is going to do to prevent suicide and reduce suicide rates. Since its creation there has not been any new strategy and actions other than following and promoting the mental illness approach (see Shahtahmasebi 2019b, 2022). This makes the other two elements of “using evidence to make a difference”, and “evaluation and monitoring” a flight of fancy and a waste of resources. For example, in the “Every Life Matters” framework (Ministry of Health 2019), suicide prevention is stated as “promotion: promoting wellbeing”, “prevention: responding to suicide distress”, “intervention: responding to suicidal behaviour”, and “postvention: supporting after a suicide”. In this document, wellbeing is not defined and ignores the ever changing socio-economic and socio-political landscape, e.g. covid19, cost of living crisis, housing crisis. Furthermore, the actions proposed in this document can only be operationalised after a suicidal behaviour has manifested which means time to apply an intervention. Thus this policy is nothing more than “more of the same” failed mental illness intervention.

The draft consultation policy plan 2025-29 (Ministry of Health 2024), is ostensibly a statement of the government’s action plan rather than a consultation document. It claims that “we have a stronger suicide prevention system, and people have access to more and better supports, services, resources and tools to support their wellbeing and respond to their needs.” There is no evidence provided to support the many claims of improvement in service provision and service uptake, and, furthermore, there is no discussion of how the claimed improvements may translate to reductions in suicide rates and suicide trends. There are only media reports of how the mental illness interventions might be irrelevant and inappropriate e.g. the case of a case seeking help after a suicide attempt (‘There is nothing here’ – Wānaka woman in mental health crisis made to feel like a burden) does not provide any reassurance that there has been improvements in service development and service delivery.

It also lists a number of “insights”, including a collective effort to suicide prevention, talking about suicide, access to supports, and using data and evidence. The suicide support services are mental illness-based intervention services and therefore the idea of a collective effort is encouraging a greater collaboration between the health agencies which provide support. Therefore this strategy does not offer anything new and appropriate (Shahtahmasebi 2013). We should certainly talk about suicide, we should certainly have competent well-funded, well-resourced and responsive mental health services, and we should certainly remove the blinkers and take serious note of the evidence. Only then can a policy that promotes collective participation, the role of a workforce, public discussion of suicide make the suicide prevention policy development more sensitive and relevant to preventing suicide.

Every suicide intervention support that the government has provided and is proposing to provide can only be “accessed” if and only if suicidality is present. How does waiting to be suicidal and then seek help prevent suicide, particularly young people, of those who die whilst under treatment, those who chose death in isolation, those who do not wish to be labelled mentally ill, those who show non-mental illness signs which were missed because no one talks about suicide? The idea of suicide prevention is to discredit suicide socially and remove it as a viable option/solution to a problem.

I have previously discussed these issues and the fundamentals of a working suicide prevention policy (e.g. see Shahtahmasebi, 2013) – all issues considered, the government’s suicide prevention policy 2025-29 is not prevention, nor will it meet the criteria for an intervention plan.

References

Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (June 2018) Suicide rising across the US. Vital Signs. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/index.html on 2018-10-30

Ministry of Health. 2024. Draft Suicide Prevention Action Plan for 2025–2029: Public consultation document. Wellington: Ministry of Health. [https://www.health.govt.nz/publications/draft-suicide-prevention-action-plan-for-2025-2029-public-consultation-document] First accessed April 4, 2025.

Ministry of Health. 2019. Every Life Matters – He Tapu te Oranga o ia Tangata: Suicide Prevention Strategy 2019–2029 and Suicide Prevention Action Plan 2019–2024 for Aotearoa New Zealand. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2022) Editorial: Suicide, Covid-19, failing health and social policies: a government out of touch. Dynamics of Human Health (DHH), 9(1): https:www.journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=2746

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2019a). Suicide prevention: flawed politics and gimmicks. DHH; 6(3):http://www.journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=1876.

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2019b) Editorial: Politics of Suicide Prevention Revisited. DHH, 6(1): http://www.journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=1740

Shahtahmasebi, S. (2013). De-politicizing youth suicide prevention. Front. Pediatr, 1(8), http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fped.2013.00008/abstract. doi: 10.3389/fped.2013.00008

Shahtahmasebi, Said & Gregory-Allen, Russell (2023). Conceptualising suicide prevention. DHH, 10(1): https://journalofhealth.co.nz/?page_id=2966.

Pridmore, Saxby & Rostami, Reza (2020). Suicidal Behaviour Disorder: a bad idea. In Shahtahmasebi & Omar (EDs). The Broader View of Suicide (2020). Cambridge Scholar Publishing; UK:pp(265-279).

WHO (2014) Preventing Suicide: A Global imperative. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/ on 2018-10-30.